Our takeaways:

- Breasts are constantly changing throughout our lives due to hormone fluctuations.

- The size of our breasts does not affect the quantity or quality of our milk.

- Some people may notice nipple discharge during their second trimester. For others, this may not occur until the third trimester or after labor.

- While our bodies are making milk, proteins, sugars, and fat are taken from our blood supply.

- Fore-milk and hind-milk are not two distinct kinds of milk.

Feeding a baby is no easy job – at least for many expectant/new moms, we are prepared for this well-known fact. What we are not prepared for, oftentimes, is EVERYTHING else about feeding our babies. From what nutrients our babies need as they grow, to what we are able to provide accordingly; from how much and how often to feed, to how to balance the supply and demand with other duties in life. It turns out that while feeding babies is mothers’ nature, the process is often not “natural” and takes both moms and their babies to learn together.

Admittedly, there’s a long-lasting debate on breastfeeding versus formula. Before we even consider either though, let’s start from the basics: our human bodies. Because knowing the basics about our bodies, including how they function by themselves, in response to our babies and external factors, will eventually help us make informed decisions on our feeding options.

Breasts basics

1. The origin: Breasts are complicated and fascinating organs. We came into the world with nipples and some cells behind them, which given the right hormonal stimulation, will grow and become breasts. (Source: Dr. Susan Love’s Breast Book)

2. The composition: Breasts are made of “adipose tissue (a.k.a. fat); stroma, the beautifully named network of ligaments and connective tissue; clusters of milk-producing alveoli cells; and a series of ducts to transport milk. Hundreds of alveoli cells gather into grapelike bunches called lobules, and groups of these lobules come together to form a lobe. The average breast is made up of 12-20 lobes…” (Source: Like A Mother: A Feminist Journey Through The Science and Culture of Pregnancy, Angela Garbes. Get this book for FREE through Kindle Unlimited). Milk leaves the nipple through a series of between 4 and 18 tiny holes called milk duct orifices or nipple pores. Some are located in the center of the nipple, while others are around the outside of it. Milk duct orifices even have their own little sphincters to keep milk from leaking out. (Source: Visible Body)

3. The function: Breasts are wired to make food for our offspring. Pregnancy affects levels of the hormones estrogen and progesterone in our bodies. Estrogen stimulates the growth of the breast duct cells and generates the secretion of prolactin, another hormone. Prolactin stimulates breast enlargement and milk production. Progesterone supports the formation and growth of milk-producing cells within the glands of the breasts. After delivery, estrogen and progesterone levels plummet, and prolactin levels rise, allowing lactation to occur. (Source: Healthline)

4. The sizes and shapes: Breasts are constantly changing throughout our lives due to hormone fluctuations. Note that the size of your breasts does not affect your ability to breastfeed. Women with small breasts make the same quantity and quality of milk as women with larger breasts. (Source: WIC Breastfeeding Support Program by USDA)

Breasts and pregnancy

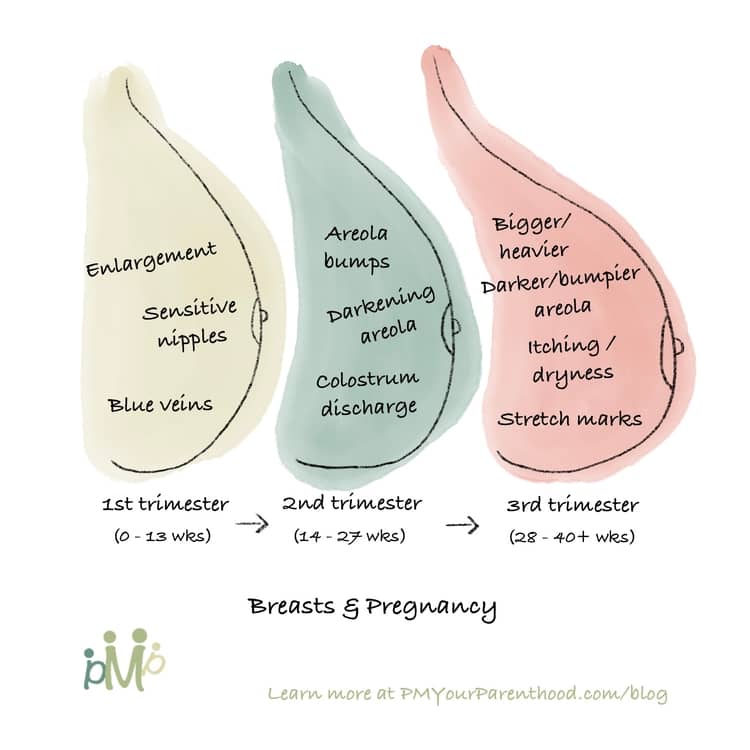

For many women, changes to the breasts are one of the earliest signs of pregnancy (Although pregnancy tests are still the most reliable way for pregnancy detection). These changes include breast swelling, soreness or tenderness, heavy feeling, or a feeling of fullness. And your breasts will continue to change as your pregnancy progresses. (Sources: Medical News Today, Healthline)

1. First trimester (0-13 weeks)

- Enlargement. Going up a cup size or two is normal, especially during a first pregnancy. This growth can begin early on in pregnancy and continue throughout. Rapid growth can cause the breasts to feel itchy as the skin stretches.

- Blue veins. Blood volume typically increases by 50% throughout pregnancy. As a result, prominent blue veins usually appear on several areas of the skin, including the breasts.

- Increasingly sensitive nipples. You may feel even painful to touch them.

2. Second trimester (14-27 weeks)

- Darkening and bumpy areola. Darkening areolas are likely to result from hormonal changes. Often, the areola returns to its pre-pregnancy color after breastfeeding, but it sometimes remains a shade or two darker than it was originally. Areola bumps or Montgomery’s tubercles (the openings of the areolar glands out onto the skin) commonly become more pronounced during this stage. These small, painless bumps have antiseptic and lubricating qualities and help support breastfeeding.

- Nipple discharge of colostrum. Some people may notice nipple discharge during their second trimester. For others, this may not occur until the third trimester or after labor. This thick, yellow discharge is colostrum, a liquid that boosts the immune function of newborns in the very early stages of breastfeeding. Discharge can occur at any time but is more likely when the breasts become stimulated. (Be careful to avoid overstimulating the nipple as it could put you into premature labor). Remember don’t be concerned that you are “using up” your baby’s colostrum if you do discharge. In case you don’t discharge, on the other hand, it doesn’t mean that you’ll have a low supply of breast milk either. Every woman’s body responds differently to pregnancy.

3. Third trimester (28-40 weeks)

- Changes you encountered during the 1st and 2nd trimesters will likely continue, but at a larger scale. Bigger and heavier breasts, darker and bumpier areola, and more regular colostrum discharges.

- Itching, dryness, and stretch marks may appear as the skin on your breasts tries to keep up with the rapid growth. Most commonly, stretch marks will show up in month 6 or 7 of your pregnancy – if they ever show up (Research indicates that 50–90% of pregnant people develop stretch marks).

Breast milk basics

1. The making: We’ve learned about the grapelike sacs called alveoli. Prompted by the hormone prolactin, the alveoli take proteins, sugars, and fat from our blood supply and make breast milk. A network of cells surrounding the alveoli squeeze the glands and push the milk out into the ductules. (Source: Babycenter)

2. The delivery: When baby suckles, it sends a message to our brain. The brain then signals the hormones, prolactin and oxytocin to be released. Prolactin causes the alveoli to begin making milk. Oxytocin causes muscles around the alveoli to squeeze milk out through the milk ducts. When milk is released, it is called the let-down reflex. This reflex and the negative pressure created by the baby’s suckling deliver the milk to the baby’s mouth. (Source: Babycenter, WIC Breastfeeding Support Program)

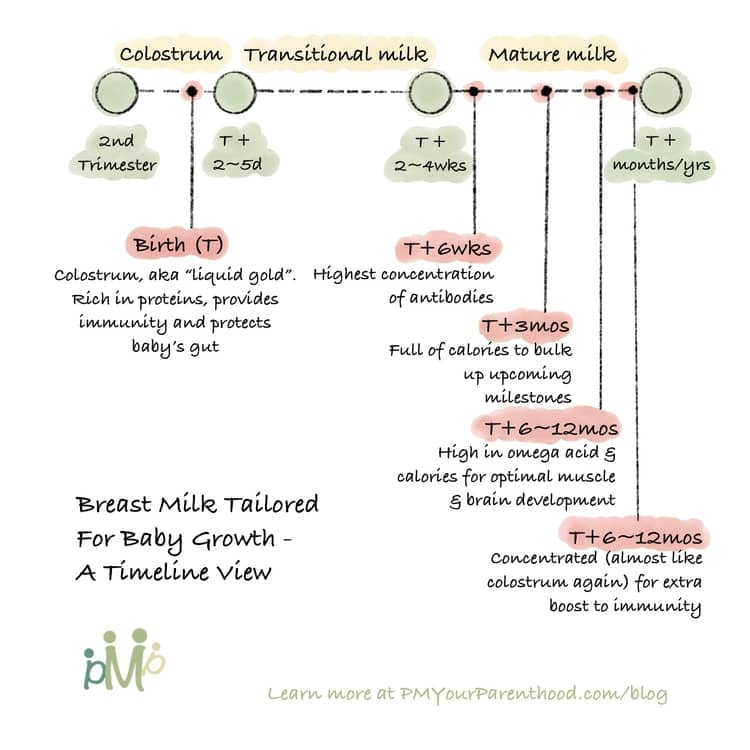

3. The stages and personalization: there are three distinct stages of breast milk tailored for the baby’s growth (Source: American Pregnancy Association).

Colostrum. As mentioned above, during them 2nd trimester, some of us will discharge colostrum that is the first stage of breast milk. It occurs as soon as 2nd trimester and lasts for several days after the birth of the baby. In terms of color, it is either yellowish or creamy, and much thicker than the milk produced in later stages. Colostrum, also known as “liquid gold”, is high in protein and plays a key role in providing immunity and protecting the baby’s gut.

Transitional milk. Two to five days after birth, transitional milk will replace colostrum and lasts for approximately two weeks. The content of transitional milk includes high levels of fat, lactose, and water-soluble vitamins, and it contains more calories than colostrum.

Mature milk is the final milk that we produce. 90% of it is water, which is necessary to keep the baby hydrated. The other 10% is comprised of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats which are necessary for both growth and energy.

- Fore-milk vs Hind-milk: Foremilk is the first milk that your baby gets at the beginning of a nursing session, and hindmilk is the milk that s/he gets towards the end of a nursing session. There’s often a misunderstanding that these are two different kinds of milk, which is not true. The milk-making cells in your breasts all produce the same kind of milk. As milk is made, fat sticks to the sides of the milk-making cells and the watery part of the milk moves down the ducts toward our nipple, where it mixes with any milk left there from the last feed. The longer the time between feeds, the more diluted the leftover milk becomes. This ‘watery’ fore-milk has a higher lactose content and less fat than the milk stored in the milk-making cells higher up in your breast. (Source: La Leche League)

- Morning milk vs Night milk: Studies show that morning levels of cortisol – a hormone that promotes alertness – are three times higher in morning milk than in evening milk. Melatonin, which promotes sleep and digestion, can barely be detected in daytime milk, but rises in the evening and peaks around midnight. While the health indications of different ingredients found in morning versus night milk are still surprisingly understudied, the general recommendations tend to side with feeding babies with time-matching pumped milk.

Some final words

Up until this point, we’ve reviewed the basics about our nursing body – specifically the complicated yet fascinating breasts and breast milk. I know these alone are not enough for us to say whether we’d prefer breast feed or formula but if you are reading this, you are getting a great start!

In a follow-up article, I will compile and share more data-driven evidence on both feeding options. Stay tuned!

Like this article? Share it with your loved ones! To get bite-size parenthood wisdom like this, or save infographics for future references, follow us on Instagram (@PMYourParenthood)!

Support me and my work by contributing a cup of coffee here: